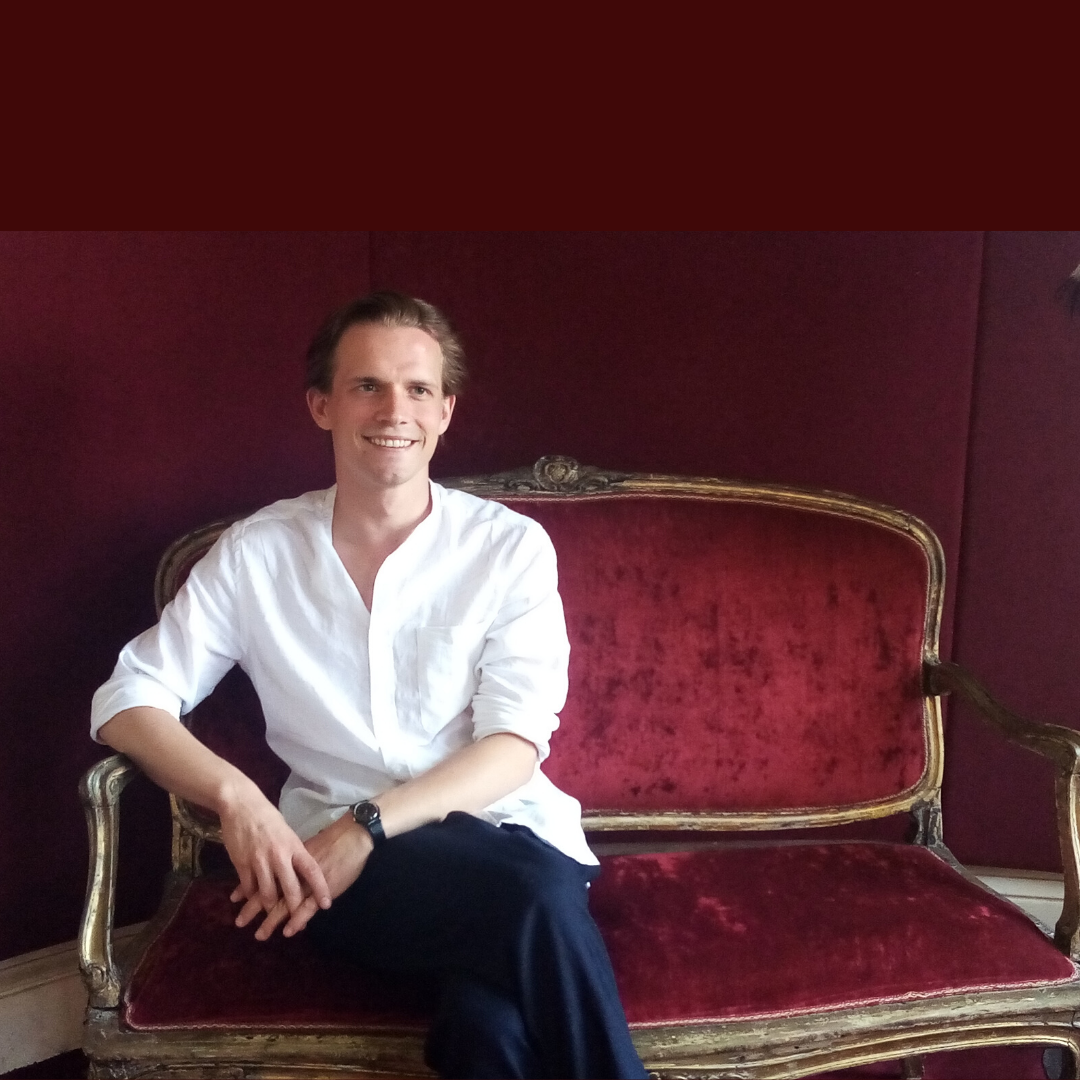

One concert and two opportunities to experience it. For the first time, the Rijeka Symphony Orchestra is being conducted by the young maestro Valentin Egel, the winner of many important competitions. On the occasion of the symphony concert “From the New World”, we spoke with the “precise and unpretentious” German conductor “of special strength and exuberant interpretation,” who brings music “emotionally, strongly, and vividly, while constantly listening to the orchestra” and who is able to extract the “best from it and arouse emotions in the audience.”

You will be performing Mozart’s Ninth Symphony, which he composed at the age of 12. It is rarely performed and not much is known about it, except that it is as ingenious as all of Mozart’s works.

The performed Mozart symphonies are normally the last three: 39, 40 and 41. There are also some earlier symphonies with names and stories: the “Linz” Symphony, or the “Haffner” Symphony. We don’t know much about this Ninth Symphony. He was basically a child who might have just kissed his first girl; you can feel this cheekiness somehow. And yet, as always with Mozart, it’s incredibly good music. It’s pure and beautiful. Everything is in its right place and it’s like a miracle. It’s exciting that we will perform this piece before the audience in Rijeka. When you perform something for the first time or at least for the first time in many years, it’s as if you are listening to new music, but from back then. It gives us the chance to be very open. When we hear a symphony for the third, fourth, fifth time, we know what to expect and recognize what is different. In this case we are unencumbered by this expectation, so we are not focused on how the symphony is played but rather what the music will give us. It’s very short, basically like an overture, but it has four movements. It has trumpets and timpani, a minuetto, a slow movement and a big finale. You start, you enjoy it, and it’s over.

Compared to Mozart’s Ninth, we know more about Dvořák’s symphony. Or we just think we do.

There’s a lot to tell about Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony, but there’s a lot untold about it. Even in essential literature about it, the first things you read about it are inaccurate. Claims are made that are just not true, such as that it was composed under the influence of African American and Native American populations. There might be some influences, but it is much more the Slavonic person in America who is homesick. More than anything, “From the New World” is a nostalgic symphony about a man far away from home who remembers tunes from the Czech Republic.

Then how did it become an American national symphony?

Because it was written in America. I wouldn’t go deeper into that. I don’t want to get into the politics of it; I just want to talk about music. For me, it’s rather like very genuine Czech music, written far from home. Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony provides so many new things not found in his earlier works. It has a certain unity, an obvious example for which is the theme from the first movement, which appears again in the next three, and the themes from all the movements come together in the fourth. The whole structure of the composition is incredible.

Are you conducting the symphony “From the New World” for the first time?

I’m not an old conductor, but I have done this piece a lot. Every time you open the score for this piece, you’ll find something you haven’t seen before on almost every page. It’s so full of detail that you can decide to focus on something different in each rehearsal and choose which parts to bring out because every tiny bit in the whole score is beautiful and worth being heard.

So it’s a challenging piece for the conductor and orchestra?

It’s a challenging task for the conductor and for the orchestra, because you are playing a piece which has been played so many times. At the same time, many details aren’t difficult; you just have to decide what to focus on, how to put a different light on certain details, and how to read a piece after it’s been done so many times.

How do you feel in Rijeka, with the Rijeka Symphony Orchestra?

It’s really great! As a German, just being in this place is incredible, this beautiful town with its marvelous landscape. It’s been great work with the Rijeka Symphony Orchestra. The musicians are passionate about what they do, and really want to create good music. Often musicians in certain orchestras simply do — they do rehearsals, they do concerts — and you have the feeling that you have to fight for passion, which really isn’t the case here. They play with great dedication and give a lot, which is very enjoyable.

It’s said that you’re a maestro of particular strength, emotiveness and precision. As a young conductor who often stands in front of new musicians you need to lead, how do you view your profession?

I don’t consider the conductor as someone in charge. Authority can be acquired in two ways:

First, you have to be well-prepared, and you have to have more information than the others about what’s happening. The other thing is not to think of conducting as one person standing in front and deciding everything, but one person influencing the people and being influenced by the people. Conducting is a two-way thing. For example, in rehearsal the concertmaster approached me with an idea, which I considered and accepted. It’s teamwork, and there is also quite a bit of nonverbal communication and energy. I constantly check with my eyes to make sure we understand each other. I follow their signals. Yes, the conductor decides what kind of music he will provide in the end. But I really believe it’s about mutual responsibility. For example, if I just dictate that the beat needs to be quicker, it will not be beautiful if I have to force that on the orchestra. They might do it, but music is all about emotion, isn’t it? We all need to be on the same side emotionally. You can’t force your ideas on the orchestra and experience them as someone from the other side. The conductor needs to get the orchestra to the point that, in the best case, the musicians want the same as you, that your way and their way is the same.

Did you learn from mentors through musical education or did you find that within yourself?

I had great mentors and I’m very thankful for them, especially the one who taught this philosophy of communication as a conductor. I also learned a lot from my father, who was a violin professor. Also, I’m the youngest of eight children, which makes you learn how diplomacy works. I would say it’s learning from other people and from experience. Even in every single rehearsal I’m learning something new, and figuring out what works best. I am looking forward to the concert!

Interviewed by Andrea Labik