Premiere OPERA AFTER KAMOVZoran Juranić

Riječki simfonijski orkestar

Riječki operni zbor

Zoran Juranić has composed around 50 works in the field of orchestral, chamber, piano and vocal music. Not long ago, the discovery of a hitherto unknown libretto written by Janko Polić Kamov for his brother Milutin intrigued the Croatian cultural public. Although it is not originally Kamov’s story (the libretto was written based on the content of Derečin’s play The Blind Man’s Love), Kamov’s text titled When the Blind See has all the features of a messy and direct author’s narration, and also demonstrates a very good understanding of the rules of veristic librettism.

Since Milutin Polić’s tragic fate prevented him from writing the opera, by setting this text to music, Juranć wishes to contribute to the memory of the Polić brothers and their accident, which is why some of the motifs and drafts for the opera that Milutin managed to write are preserved in the score. The opera is preceded by the Prologue, which premiered at the Rijeka 2020 – European Capital of Culture opening ceremony. In this “Kamovljev Credo,” the writer deals with the main themes of the poetic mainstream of the time – love and national enthusiasm, as well as superficial social motives.

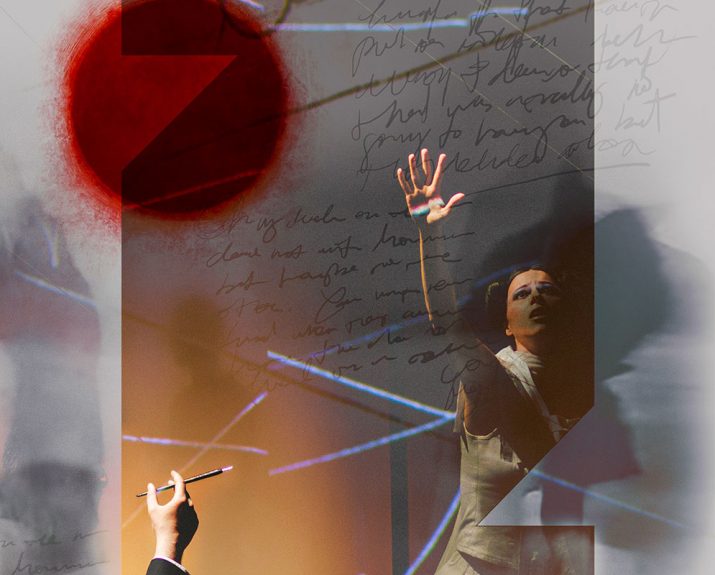

The director points out that “in all his poetic, literary and theatrical productions, Janko Polić Kamov speaks in the first person. His thoughts, torments, body, lust and anger are the substance from which his verses are created. There is no place in his characters for civic drama, verismo, or even human psychology: they are the embodiment of his writing – characters made with words.”

Written in blood ink

In his whole poetic, literary, and theatrical production, Janko Polić Kamov speaks in the first person. His thoughts, torments, body, lust, and fury are the substance of which his verses are made. Even his corporal secretions are the subject of his writing, as every aspect of life’s experience becomes concrete material on the white page.

Although there are no direct references to his private life’s events, we can see through the scripts the traces of the significant circumstances leaving a mark in his existence. The original libretto narrates about Ivo, a man who became blind and his friend, the painter Robert. In the center of the plot, the wife of the blind man, Maja, is struggling between the sense of duty and the fascination of a prismatic universe. The storyline is counterbalanced by two other characters: Ivo’s mother, the severe and gloomy Ana, and the ambiguous and puzzling Pajo… Despite the plot’s structure’s appearance, the main character is the WORD.

Kamov’s writing overflows on the page, stands above the story self, rules. There is not space for a bourgeois drama, verismo, or even for human psychology in the characters: they become the personification of his writing—figures made by words. Kamov’s language’s apocalyptic wealth builds a symbolic universe around the characters raising the storytelling to an immense metaphoric play.

If we accidentally juxtapose to the plot some facts of the author’s private life, all at once, an astounding x-ray appears. What if we overlap Kamov’s beloved Katarina (mentioned as Kitty in many poems) with the character of Maja? What if we realize that Robert the painter expresses his passionate and fascinating creativity not with a brush but just through words? What if we read the relation between Robert and Ivo as a translation of the friendship between Kamov and his best friend Mato Malinar, who married Katarina? The whole story’s perspective changes; the overlapping becomes a prism that enlightens every lack of realism or psychology, giving us the access key to penetrating the figurative language’s thickness.

The bound with the writing material – the ink, the paper – is the essential substance in Kamov’s creative process. The opera Prologue (composed on the text of the poem “Post-scriptum”) introduces the controversial relationship between the poet and his writing. Pajo’s character – the cynically bitter reporter of the story – stands alongside a wild creature, an allegorical personification of Kamov’s visceral writing. A skein of words struggles to look for an identity with the author’s shadow behind. The Prologue and the Opera, connected through Pajo’s eyes as Kamov self, become a flow of multiples layers: the symbolic strength of the text, the see-through of touching episodes of the poet’s life, an inner journey of the author self as narrator, viewer, mastermind. The poet’s pulse rate is the rhythm of a story written in blood. If not even in his veins, the ink flowed straight away.